film supports

1 Nitrate Film | 2 Acetate Film | 3 Polyester Film | 4 Structural Layers | 5 Final Image Materials

Like photographic prints and glass negatives, film-based media are composite objects, consisting of a film support and a binder/emulsion layer with an image-forming or recording substance suspended in it. Film has been used as a support for many different types of media since the late 19th century, including various types of still photography film, slide film, microfilm, amateur movie film (8mm and 16mm), and motion picture film.

Three types of film have been used as supports: nitrate, acetate, and polyester films (with the latter being the most stable). Many modern film-based media use a polyester film base, but not all. The characteristic deterioration of these films will be discussed in this section, along with typical deterioration mechanisms of the binder and image-forming materials.

Film is also used as a base for magnetic tape (audio, video, and computer tape), which is discussed in Session 6: Media Collections.

1 Nitrate Film

Nitrate film was invented in the late 19th century in response to the need for a more lightweight and less fragile support for photographic negatives. The first nitrate sheet film negatives were made from celluloid (a primitive form of plastic made from cellulose nitrate combined with a plasticizer). Celluloid was first created in 1846 and was used for many purposes, including making billiard balls and combs. In 1887, the first sheet film negatives were made by coating a thick sheet of celluloid with a layer of gelatin emulsion. Within a few years, gelatin emulsion roll film made from a thinner and more flexible form of celluloid became available.

Cellulose nitrate film was used as the support for many different types of film, including portrait and commercial sheet film, x-ray film, 35mm roll film, and motion picture film. It was not used for color film or for 16mm or 8mm film (both of which were made for the home and educational markets). Nitrate film was eventually supplanted by cellulose acetate film, and the Eastman Kodak Company stopped producing nitrate film completely in 1951.

Characteristic Types of Deterioration

Nitrate film is extremely flammable, which eventually led to its discontinuation and replacement by cellulose acetate film. Its chemical instability was less apparent at first, but six progressive stages of its deterioration have been extensively documented over the years:

- No deterioration.

This nitrate negative is in Stage 3 of deterioration. Light box displaying a nitrate photograph negative panorama, Library and Archives Canada [flickr]. - The film turns yellow and the image exhibits silver mirroring.

- The film becomes sticky and gives off a strong nitric acid odor.

- The film turns an amber color and the silver image begins to fade.

- The film becomes soft and may adhere to adjacent materials, and the image becomes illegible.

- The film breaks down completely, turning into a brown powder.

Early nitrate roll films tend to curl very tightly; in 1903, manufacturers began to coat the reverse side of the film with gelatin to prevent this problem

The chemical decay of nitrate film is irreversible and is made worse by high temperature and high relative humidity. In Session 6: Media Collections and in Session 7: Reformatting and Digitization, you will learn more about Identifying Motion Picture Films, proper Storage of Motion Picture Films, and considerations in the Reformatting of Motion Picture Films.

2 Acetate Film

Cellulose acetate film was first invented in the late 19th century to replace cellulose nitrate film, which was already recognized for its dangerous flammability. However, the first acetate was not practical for use. Acetate is an umbrella term that encompasses several different types of film: cellulose diacetate, acetate propionate, acetate butyrate, and cellulose triacetate. Cellulose diacetate was developed first and was used for both sheet and roll film between 1923 and 1955, but it had a tendency to shrink a great deal.

Acetate butyrate and propionate films were developed during the 1940s as alternatives to cellulose diacetate; these were used for home movie roll film, x-ray film, sheet film, and aerial film. Nitrate was still superior to these films, however, and used for most 35mm motion picture film.

Cellulose triacetate was developed in the late 1940s. It was used for sheet film, various sizes of roll film (particularly 8mm and 16mm, which are commonly found in cultural collections), and motion picture film. It is still used today for most types of roll film, including transparency film (slide film). During the 1970s, however, polyester film began to replace it for sheet film.

Characteristic Types of Deterioration

While cellulose acetate films do not have a problem with flammability, they are just as chemically unstable as nitrate films. The hydrolysis of acetate is referred to as "vinegar syndrome" due to the distinctive vinegar odor it produces. Vinegar syndrome proceeds quickly at room temperature, and it is accelerated by higher temperature and relative humidity. The stages of deterioration are:

- No deterioration.

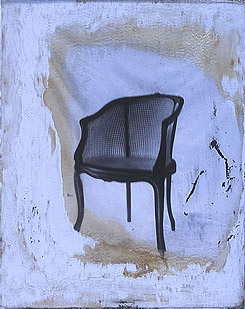

This acetate negative, in the last stage of

deterioration (Stage 6), shows channeling

where the emulsion has separated from its base. - The film gives off a vinegar odor (due to acetic acid) and begins to become brittle and shrink.

- The film begins to curl and may have blue or pink staining.

- The film loses flexibility and warps.

- The film develops liquid-filled bubbles and crystalline deposits, sometimes obscuring the image.

- As the film base continues to shrink, the emulsion becomes separated from the base in some areas, known as channeling.

The deterioration of cellulose acetate is autocatalytic, meaning that as the film becomes more acidic, this acidity further accelerates the deterioration process. Cold or frozen storage is recommended to slow deterioration. The Image Permanence Institute (IPI) has developed a product called A-D Strips that can be used to determine the extent of chemical deterioration in acetate films; see IPI's A-D Strips Web page for more information.

3 Polyester Film

Polyester film, a generic term for polyethylene terephthalate (PET), was developed in the mid-1950s. During the 1960s and 1970s, it gradually replaced acetate for sheet films. Polyethylene naphthalene (PEN, a modification of PET) was introduced in 1996 for amateur roll film, under the brand name Advantix, but other roll films are still made from cellulose acetate. Polyester film is a synthetic polymer, unlike cellulose acetate and cellulose nitrate, and it does not contain solvents or plasticizers. Thus, it is inherently very chemically stable. Polyester film is also used for archival quality enclosures for collections, which was addressed in Session 3: Caring for Collections.

Polyester is a tough, chemically stable film base, and its tensile strength lessens the likelihood of damage via handling or, in the case of motion picture films, playback.

4 Structural Layers

While degradation of the substrate is usually the primary cause of damage to film-based collections, the binders and image forming materials are also subject to deterioration.

Binders/Emulsion

|

|

As discussed in the last section, collodion was used as a binder for collodion glass plate negatives and lantern slides. Gelatin was introduced about 20 years later and used for gelatin dry plate negatives and transparencies such as lantern slides and autochromes (an early color process).

Lantern slides first used an albumen binder and later wet collodion and dry gelatin binders. Since lantern slides and autochromes have a glass covering that is taped around the edges, their emulsions are somewhat more protected. However, broken tape seals and cracked or broken cover glass do occur and can allow moisture to enter and emulsions to crack and peel.

Collodion glass plate negatives sometimes had a subbing (a thin coating, usually albumen), which was applied to the glass plate to help the collodion adhere to the glass. In addition, a varnish coating was placed over the emulsion for protection, since it was very fragile and subject to abrasion. Gelatin dry plate negatives were also coated with a subbing, or they were chemically etched to help the emulsion adhere to the glass. Gelatin dry plates were usually not varnished. In general, gelatin binders are subject to softening and mold growth in high relative humidity, as well as flaking due to shrinkage of the gelatin in low relative humidity.

|

High humidity has caused the emulsion on this |

Nitrate, acetate, and polyester films all use gelatin as their binder material. Nitrate and acetate films also had a subbing of diluted cellulose nitrate to help the binder adhere to the film. In addition, nitrate (after 1903) and acetate had an anti-curl layer of gelatin applied to the back of the film. The tendency of gelatin to soften in high humidity is made worse by the byproducts of nitrate deterioration, which cause the emulsion to become very soft and sticky. In acetate and polyester films, the gelatin is vulnerable to softening and mold growth in high humidity, but is otherwise not a major contributor to deterioration.

5 Final Image Materials

Silver Particles

|

|

In black and white negatives, transparencies, and films, the image is made up of silver particles suspended in the binder material. As in photographic prints, the silver particles are formed by the exposure and development (using chemicals) of light sensitive silver salts. In gelatin dry plate negatives and collodion glass plate negatives that were not coated with a varnish to protect the image, oxidation of the image is common, resulting in silver mirroring. In nitrate film, the byproducts of deterioration cause the silver image to fade.

Color Dyes

The color dyes used in autochromes are subject to fading. Color negatives and films—which use chromogenic color dyes and were produced on acetate and polyester bases—are subject to the same problems with dye fading and highlight staining as are color photographic prints. These materials are not permanent, and some older negatives are already faded to the extent that they cannot be printed. Cold or frozen storage of color materials is recommended to slow deterioration.