Conservation Treatment, Digitization, and Rehousing

NEDCC recently conserved the Great Deed for the Town of Billerica. The treatment was prompted by the building of Billerica’s new High School, which opened in September 2019. The conceptual design was to incorporate Billerica’s substantial history into the building. A significant part of the design was to include one and two story murals of the town’s history throughout the building. Of particular interest to the high school building committee was to have a wall sized mural of the Great Deed in a conference room that would be known as the 1655 Room. The high school building committee utilized the knowledge of Local History Librarian, Kathy Meagher, to evaluate the feasibility of this idea. She—along with the Town Clerk, Shirley Schult, who oversees the safety of the town’s records—accessed the town’s vaults to examine the Deed in person rather than the black and white photocopy available digitally.

While the deed was in a leather-covered portfolio, parts of the cover were broken and the deed was very loosely hinged into the case. There were no additional protective layers or support to the piece when handling or trying to view the verso. While preventing extensive mechanical damage, the cover did not protect the object from environmental conditions and the Great Deed had severely cockled due to changes in temperature and humidity. Kathy and Shirley both agreed that the deed should be better protected and preserved given its significance to the town.

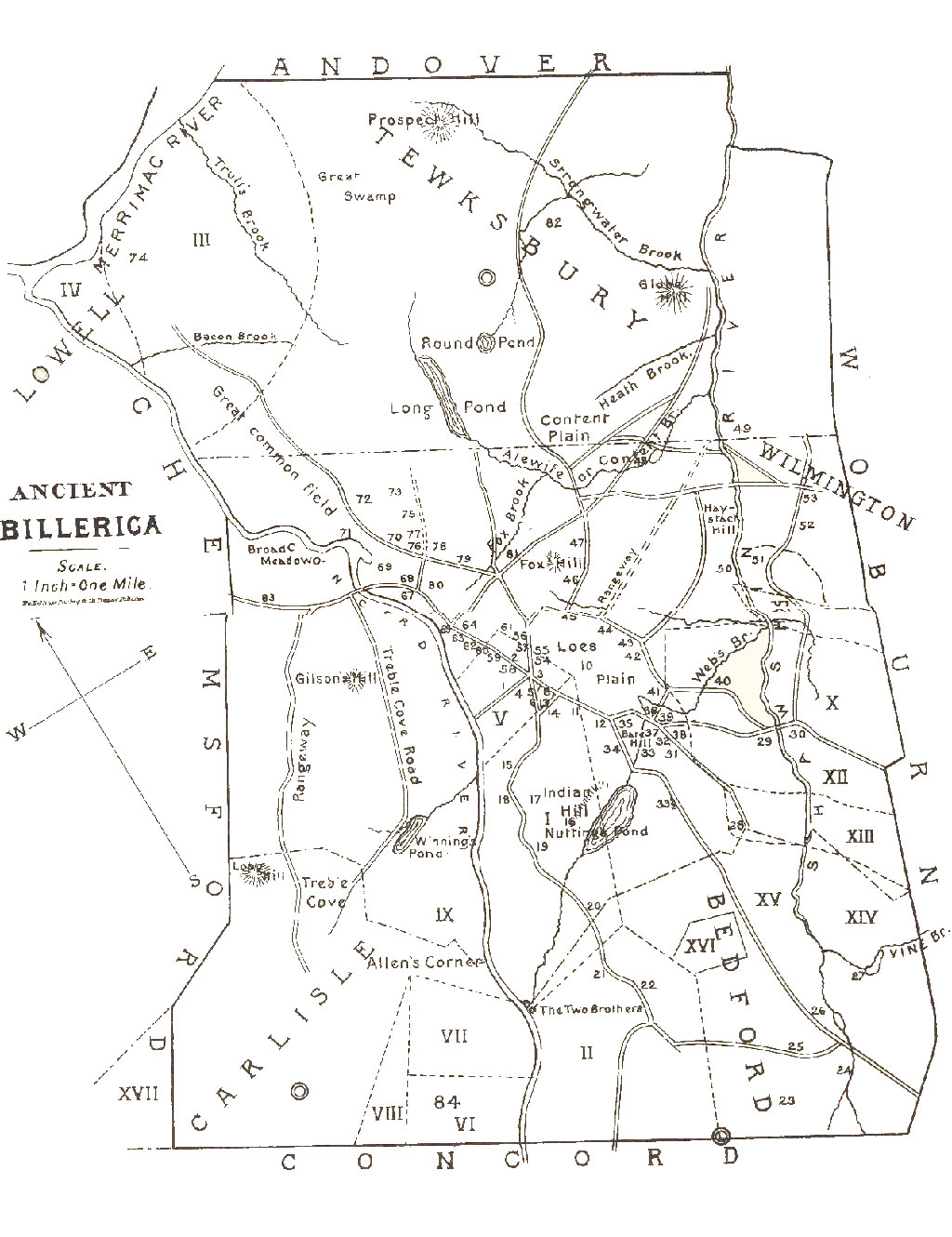

“Billerica Land Survey Map, 1760,” courtesy of the Billerica Public Library

The Establishment of a Town

Billerica’s first land grants were issued to Governor John Winthrop and Lt Governor Thomas Dudley in 1638. More land grants in this area were issued to important proprietors of Cambridge, making the Shawshin wilderness part of Cambridge. However, as more and more families settled on these grants, the need to self-govern became apparent. After a series of petitions to the court and other negotiations, the Town of Billerica was officially incorporated in 1655, though it took almost fifteen years for all the proprietor’s signatures to be collected. A final acquisition of approximately 8000 acres was agreed upon, the resulting document, “Billerica: Deed of Their Town from Cambridge Proprietors,” was created. It is more commonly referred to as “The Great Deed” by local historians and townsfolk.

The list of Cambridge grantees reads like a who’s who of the times. For example, Mrs. Winthrop, Governor Winthrop’s wife, was awarded a large grant on top of her husband’s already vast holdings. Henry Dunster, the first president of Harvard College also received a large grant. Individuals were not the only recipients, as The Church of Cambridge and its ministers were also granted land in Billerica. However, not all of these important people took up residence here. Many chose to remain in Cambridge and released their grants to residents with establishment of the Great Deed.

Of all of the signatures on the Great Deed, one of the most significant to early American history, and specifically that of Colonial New England history, is that of Thomas Danforth. Danforth was a prominent figure in the courts and politically. He held the offices of Selectman and Town Clerk of Cambridge, Assistant (one of the Council of Magistrates), Deputy Governor, President of the District of Maine, Judge of the Superior Court, Treasurer of Harvard College, Treasurer of Middlesex County and Recorder. In his position as Magistrate, Danforth was active during Salem Witch Trials, but denounced the way they were conducted and worked to bring them to an end.

Another notable signature is that of Daniel Gookin. He was Deputy to the General Court, a Selectman of Cambridge, Assistant and Superintendent of the Indians. He later wrote two books about Praying Indians, a term for Native Americans who were either willingly or unwillingly converted to Christianity.

Signatures of other important figures in early Colonial New England history are present in the lower two-thirds of the document along with even more signatures on the verso. In the mid-1700s, the land was divided into what is now known as the towns of Billerica, Bedford, Wilmington, and Tewksbury.

“Ancient Billerica,” courtesy of the Billerica Public Library

Funding for Preservation of Historic Resources

Prior to treatment, access to this important piece of the town’s history was very limited. Whenever it was viewed, the Great Deed was immediately exposed to direct dangers of the environment and of handling. This meant restricting access to the document to very serious inquiries only. Furthermore, considering the age of the Great Deed – over 360 years old – and the fact that it survived the burning of the Town Hall, they believed it was time to provide better housing to prevent future damage and offer greater protection against the elements.

In order to improve access and better protect the deed, Kathy Meagher and Shirley Schult decided to pursue Community Preservation Act (CPA) funding to treat the Great Deed and make it more accessible for the people of the town. Learn more about CPA funding.

The Great Deed of Billerica attached to its housing

The Great Deed of Billerica attached to its housing

Conservation Treatment of the Great Deed

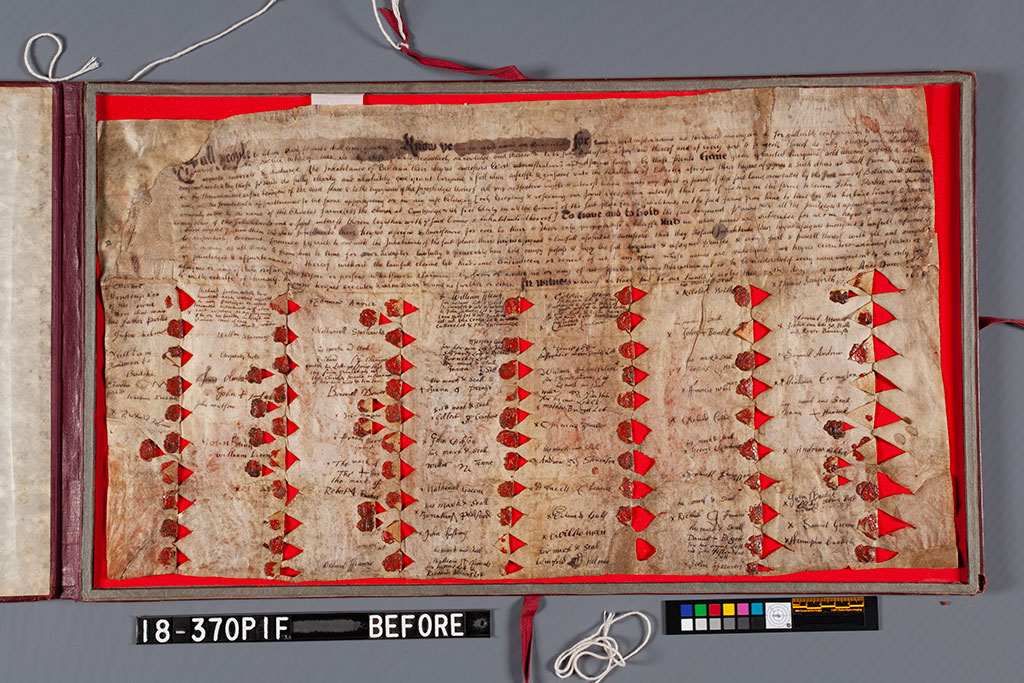

The Great Deed was housed in a full leather clamshell case with gold tooling and a red fabric interior upon its arrival to NEDCC. The date of the construction of this housing is unknown, but is believed to be sometime in the mid-20th century. The deed had been attached to the housing at the upper edge with 1” wide parchment strips. It was unclear if this was performed in tandem with the case construction or later in the deed’s history.

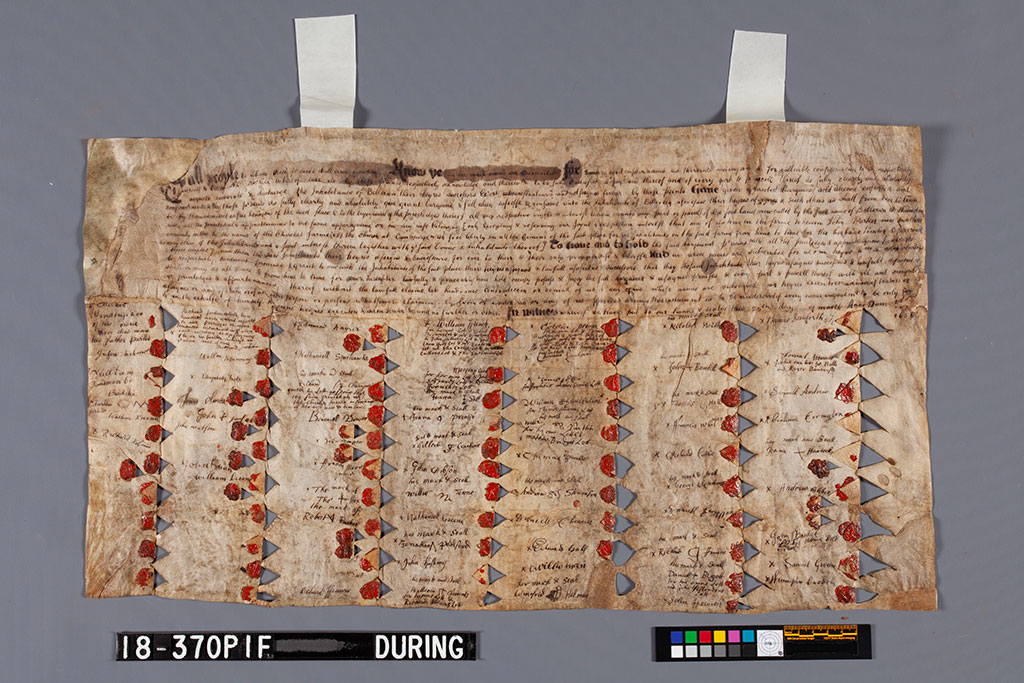

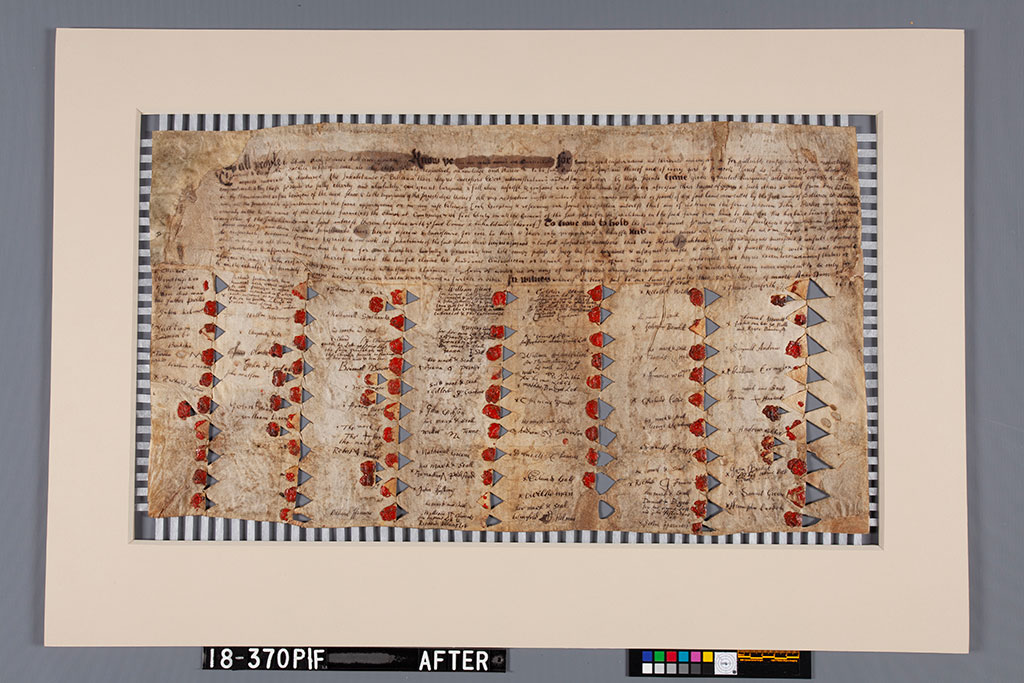

Recto of the Deed after removal from housing case

There was evidence that the Great Deed had been previously treated, and though the exact date of treatment is unknown, Billerica Town and Library staff believe it was performed in the late sixties or early seventies. Large parchment fills had been inserted throughout the document, with some fills hidden more successfully than others. The most obvious of the fills was present at the proper left of the deed (see the upper left corner in the image above), but upon closer examination somewhere between 10-15% of the document was believed to have been repaired in this manner.

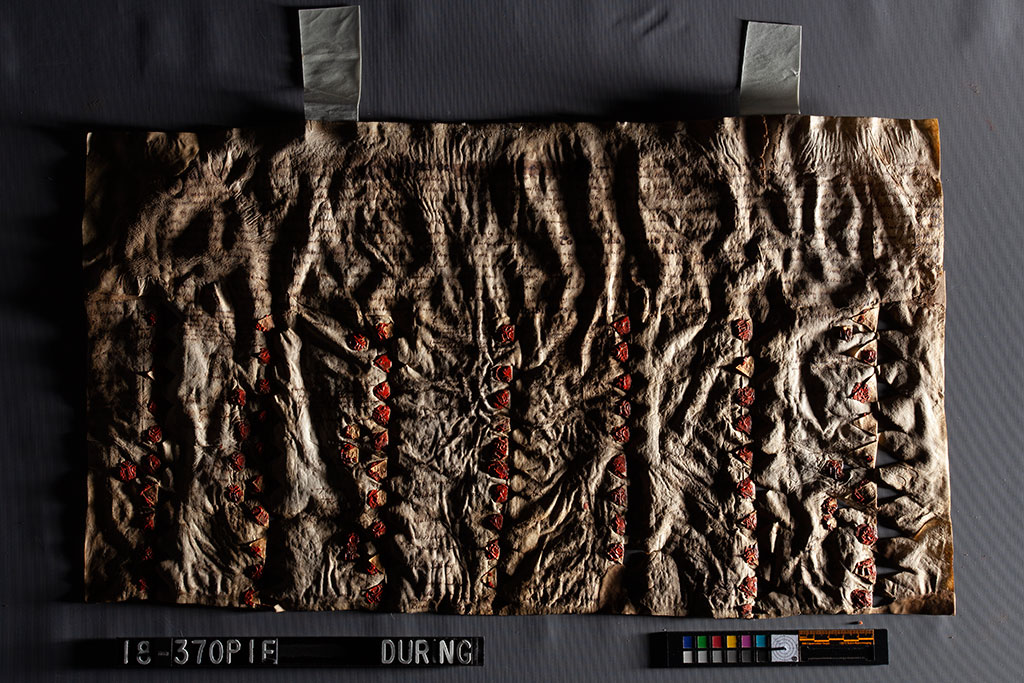

Due to the nature of parchment and how it reacts to environmental changes, the original parchment and historic repair parchment were in conflict with one another. These conflicting forces, combined with the numerous voids and seals, caused the parchment to cockle and pitch in irregular ways. The extent of this damage was best observed under raking light which gave a clear map of how the parchments pulled against each other throughout its history.

The Great Deed in raking light

Further evidence of prior treatment was visible under magnification. The text had a slight sheen throughout the document and was very firmly attached. Considering the severe distortions of the document, we would typically expect the ink’s attachment to the parchment to have weakened and cause the ink to flake off. The level of adhesion observed combined with the unusual sheen suggested some form of consolidation had been performed during the prior treatment effort.

Magnified text showing sheen from previous treatment

After thoroughly examining and documenting the Great Deed and speaking with archives staff, a treatment plan was proposed that would best stabilize and house the Great Deed for future generations of Billerica’s citizens. There were further discussions regarding increasing accessibility and display of the document in public spaces. While the Billerica CPA funds did not cover the cost of digitizing and creating facsimiles of the deed, the town felt it was important to be able to display a physical copy at the Town Hall, as well as provide digital access for researchers, considering the significance of the piece to Billerica’s History.

It was agreed that due to the condition of the parchment, the way it had conformed to the historic fills, and the delicate nature of some of the fill attachments, the historic fills would not be removed. This, along with the numerous voids in the lower two-thirds of the document, would limit the extent of humidification and flattening that could be performed on the deed later in treatment.

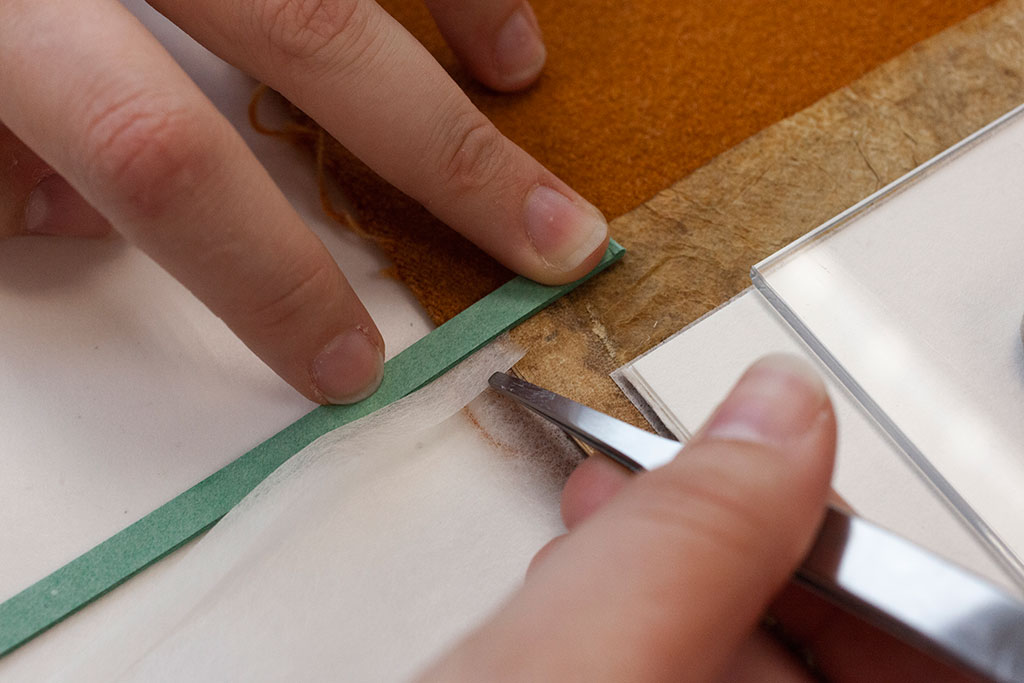

As the seals were cracked, but not actively separating from the parchment, rather than addressing the breaks, the first stage of treatment was to remove the hinging strips from the upper edge. The strips were first trimmed to the edge of the deed to remove any excess material. A 2% methylcellulose poultice was then applied on top of the remaining portion of the hinges to locally soften the attaching adhesive. The hinges were then separated from the deed using a scalpel.

Lifting hinge attachments with a scalpel after methylcellulose application

After removing the hinges, there were still some remnants of the water-soluble adhesive that needed to be removed. In the case of the left hinge, the hinge had been attached directly on top of an historic fill. In order to avoid reactivating the adhesive that was holding the historic fill in place, a 5% solution of methylcellulose was applied to the area, which allowed the adhesive to be scraped away with the scalpel without affecting the historic fill. This higher concentration of methylcellulose provided greater control over the amount of moisture released in the area of interest and gave the conservator more working time to reduce the adhesive residue.

Careful reduction and removal of adhesive residues around historic fill

Following the removal of the hinges, both sides of the Great Deed were then lightly surface cleaned with small-pore, non-latex sponges to reduce surface grime. Care was taken around the seals and voids to avoid catching the parchment in those areas.

Showing amount of removed surface grime from the lower edge of the Deed

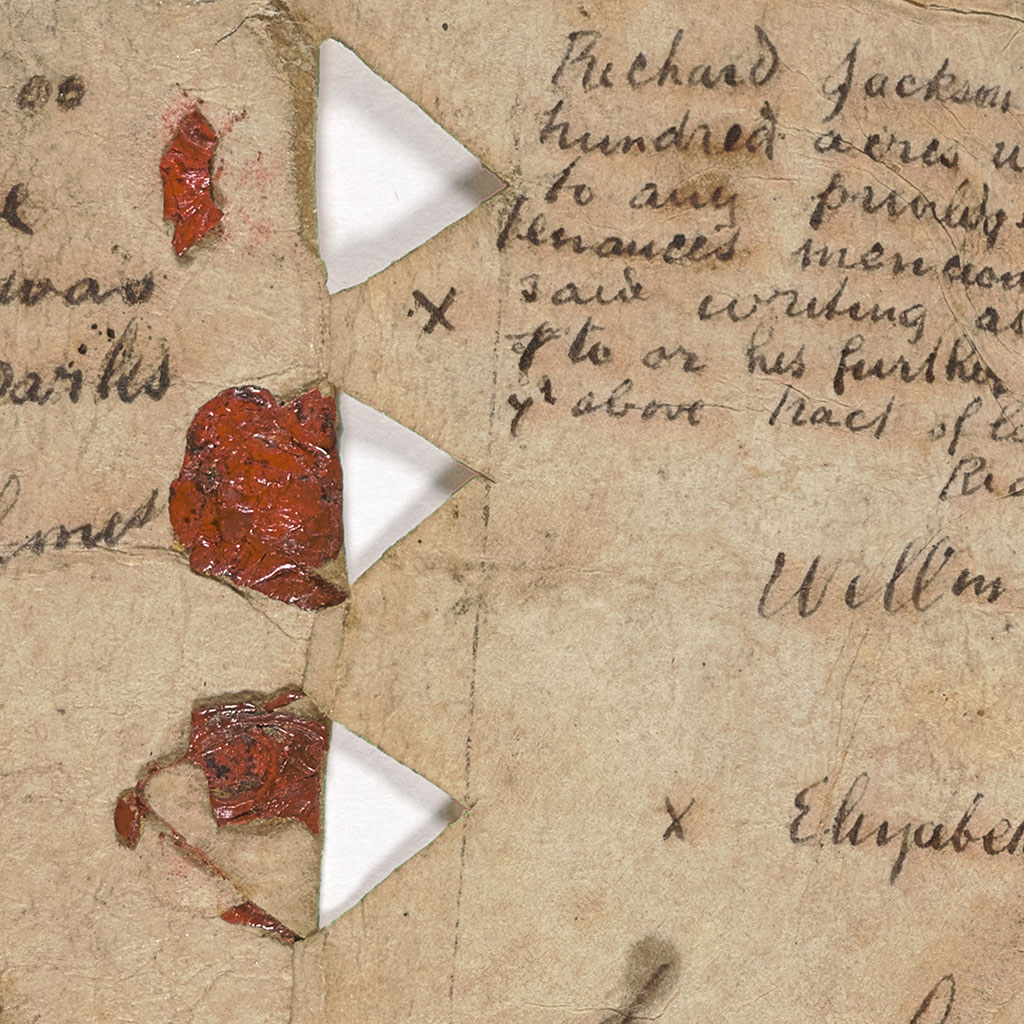

With the deed cleaned, the broken seals were then addressed. Most of the seals showed the typical cracking one would expect given the age and severe distortions on the deed, but were stable despite the breaks. However, each seal was tested to determine if the wax was completely broken or just fractured as broken seals would be at risk of detachment and loss in the future.

Testing wax fractures on seals

All fractures were first tested with a dry brush to see if the wax moved. Specifically, the conservator was looking for areas of deep breaks and pieces where wax had separated from the parchment, but were being held in place by the pressure of the surrounding wax. In such instances the wax’s tenuous attachment could lead to losses, even with minimal handling or display.

Magnification of a broken seal showing examples of typical fractures and deeper breaks

These loose areas of wax were then consolidated with a 5% solution of B-72 in acetone. B-72 is a conservation-grade acrylic resin that has both high strength and flexibility, making it an ideal stabilization material for wax in most cases. As seen in the picture above, the seals were very dirty and had a slight, irregular shine to them. This suggested that they may have been previously treated with a sealing layer at the same time as the text. The sheen and dirt were not easily removed, and as the origin of the sheen could not be definitively determined, additional local cleaning was not performed.

Brushing out Tengujo 11 gsm paper with wheat starch paste

After consolidation, local repairs to the parchment were performed by pasting out a lightweight handmade Japanese tissue paper, Tengujo 11gsm, with wheat starch paste and applying it to the damaged areas. Most of the repairs were placed near the triangular voids because their sharp points created areas of weakness that made them more susceptible to tearing and pinching.

Localized reinforcement of seal voids

Once the repairs were completely dry, the Great Deed was humidified in a packet to relax the parchment in preparation for the realignment of the creased areas. The parchment was lightly aligned by hand with local burnishing as needed and possible, then allowed to dry under thick, soft felts. While the piece was not as flat as it would have been had it been possible to humidify and stretch the skin, the preferred flattening method for parchment, it was greatly improved after this light humidification.

Great Deed in raking light after humidification and attachment of tension mounting

Digital Imaging and Creation of a Facsimile

The Great Deed was imaged using NEDCC’s XY Table with a Phase One 100-megapixel medium format camera at a resolution of 600ppi. This allowed NEDCC’s Imaging Department to create an extremely accurate digital record of not just the content, but also of the texture and nuances of the parchment and seals that would translate into the two print facsimiles for exhibit.

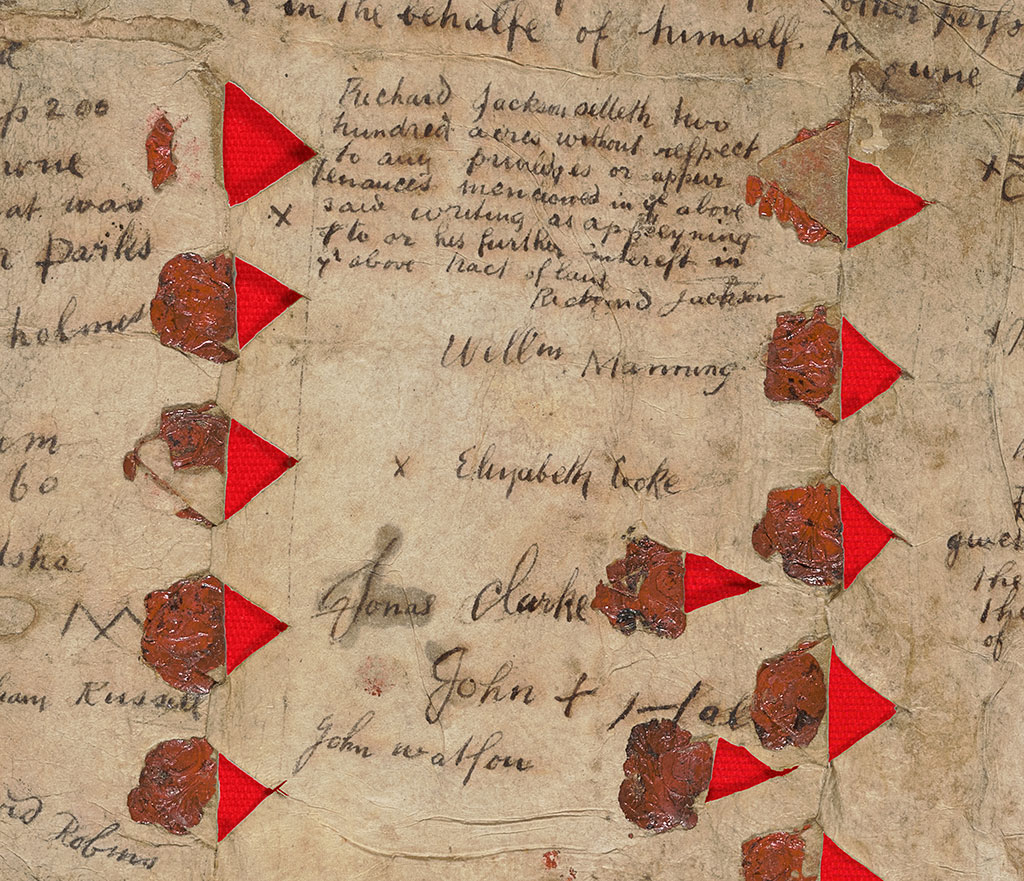

Close up of the digital access version of the Great Deed

The Town had also made a specific request regarding the background color for the facsimile. Usually, a neutral, sympathetic tone for the background fill is selected by sampling the color from an area of relatively good condition on the object. These background fills eliminate shadows and other visual distractions in the facsimile’s presentation. However, as there were numerous voids in this piece, the archivists wanted to ensure that the document read as clearly as possible while maintaining some historical context.

As most researchers and staff had always seen the deed against the red textile backing from the clamshell housing, they requested the facsimile be presented with a similarly colored background. NEDCC’S Imaging staff went beyond simply using in a color-matched red, though. The textile fabric of the case was shot at 600ppi in the same manner as the deed. This was then dropped into the background and shadows present during the original image capture were preserved to truly replicate the visual appearance of the deed against a textile backing. The only evidence that would give away the facsimile at a distance was that facsimiles of the recto and verso were matted together in a single frame.

Detail of replication of textile backing from the original housing

A New Home

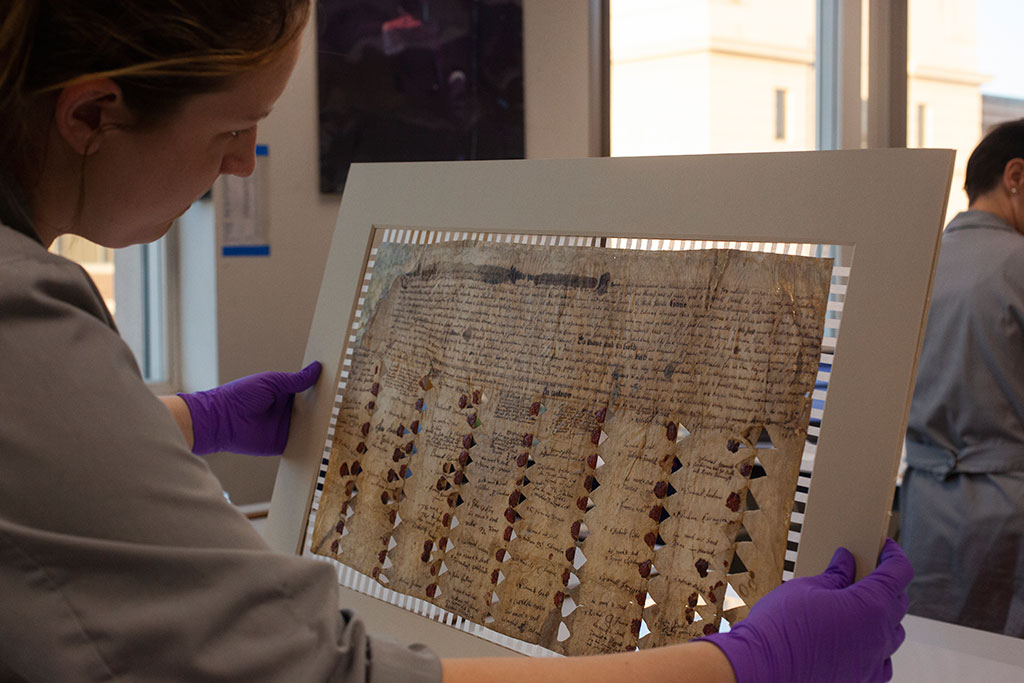

Once color matching was complete, the Great Deed could be completely rehoused. For parchment documents, tension mounting, either with linen strings or Japanese tissue paper, is recommended as it helps keep these types of documents in plane. The thought process behind tension mounting is that by having equally spaced attachments around the perimeter of the document the resulting tension will minimize the changes that parchment would normally exhibit when its exposed to fluctuations in temperature and relative humidity (RH).

Because the Great Deed was a double-sided document, the entirety of both sides needed to be visible in the frame. Additionally, because the deed was very irregularly shaped, NEDCC recommended a float mounting technique that would suspend the document in the mat using Japanese tissue paper.

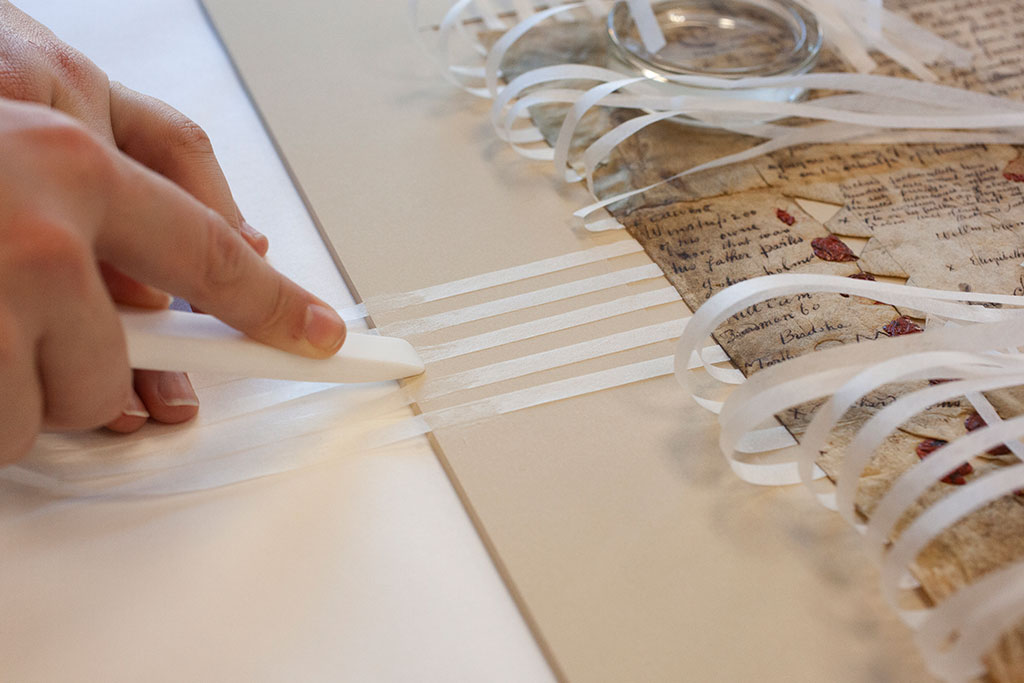

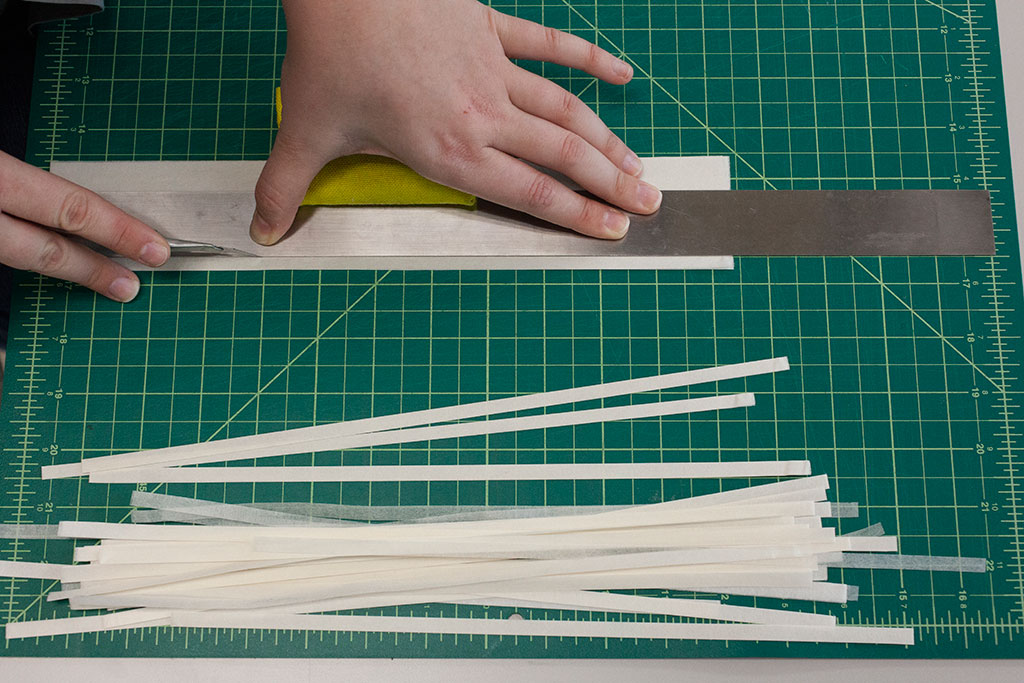

Preparing Japanese tissue paper tension strips

Preparing Japanese tissue paper tension strips

To perform the tension mount, a rolled Japanese Kozo paper weighted at 27gsm was first cut into 1/8” strips with a sharp blade. One end of each strip was then feathered for attachment to the edge of the deed. The deed was placed under light weight with blotters and felts in such a way that the perimeter was exposed.

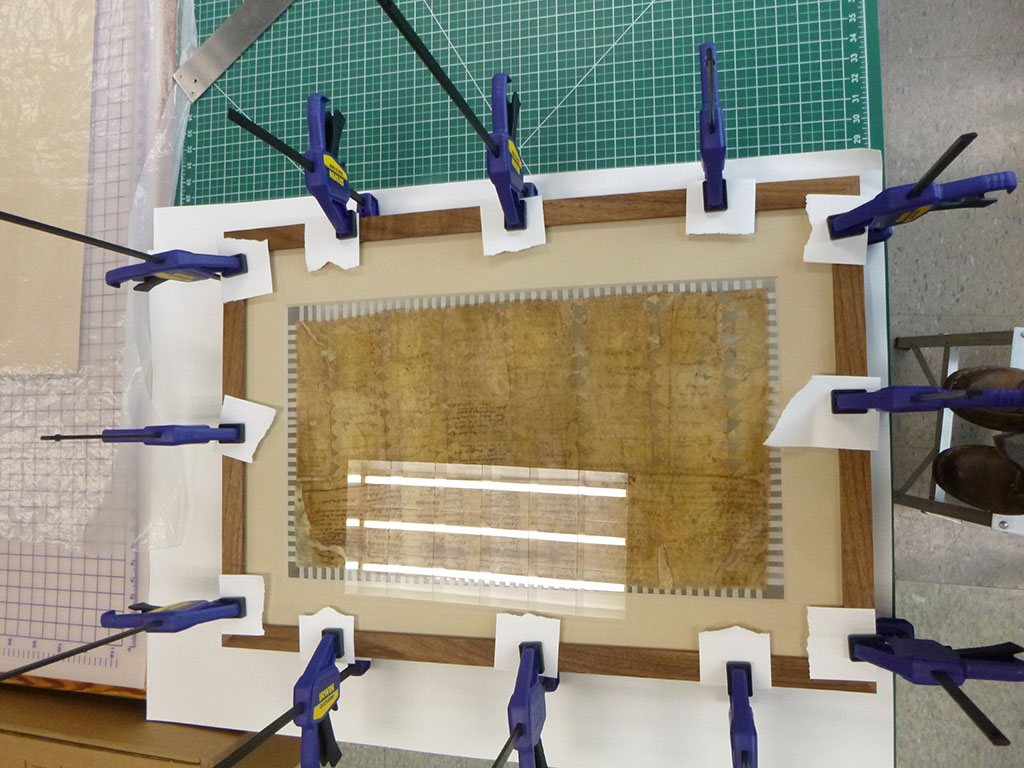

The Great Deed under light localized pressure with edges exposed for paper attachment

Using custom cut guide rulers, the strips were aligned and spaced equally around the edges. Each strip was attached using wheat starch paste and confirmed to be as square to the edge as possible before being pressed to dry in place.

Attachment of tensioning strip at one edge

Checking placement and alignment of the tensioning paper

Lightly tugging and twisting the paper to ensure they would not detach from the piece while suspended confirmed the attachment after the adhesive was dry. After all the strips were securely attached, the deed was centered for float mounting. The verso’s window mat had a support board inserted to allow for better tensioning of the Great Deed. Attachment of the tensioning strips to the mat began at the center on each side. The strips were squared up to one another and attached to the board in the margins with a mixture of 50% Jade 403 (a synthetic adhesive) and 50% wheat starch paste. The strips were then burnished and allow to dry.

Checking angle and alignment of strips on mat prior to float tensioning

Lifting and adhering tension strips to mat

Burnishing down tension strips

Once complete, the lower support piece was removed, the upper mat was attached, and the deed was checked to ensure that there was good tension overall. By holding the matted piece vertically, it could also be checked to ensure that there was no sagging or buckling of the parchment in the mount.

Testing tension and checking for sag in the float mounting

Tensioned Great Deed in mat

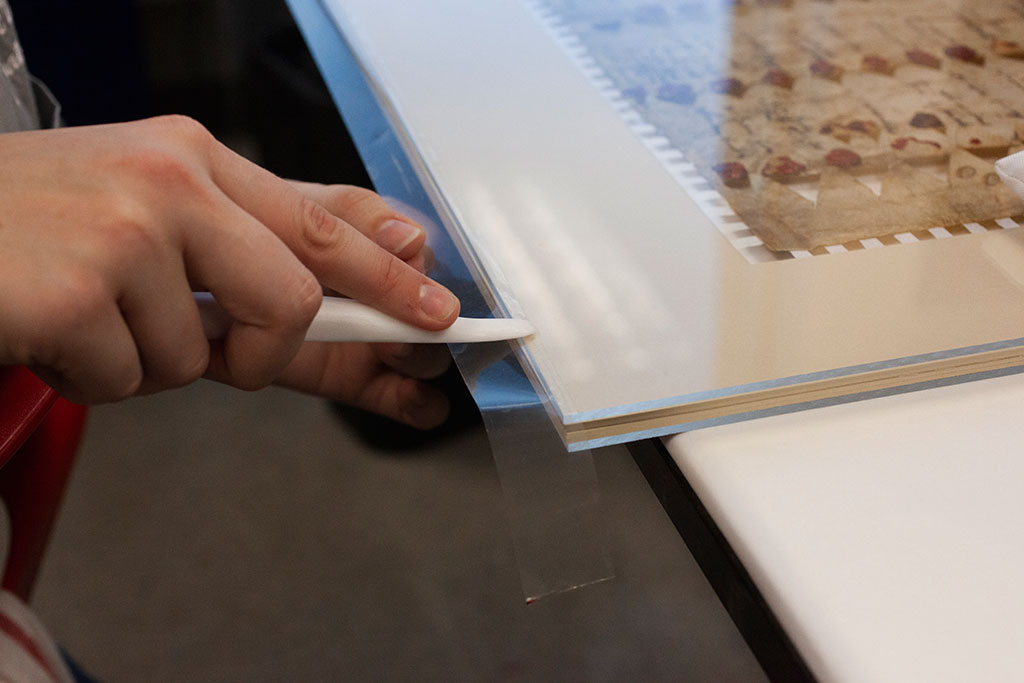

The matted deed was then sandwiched between two pieces of UV filtering acrylic and sealed with an archival sealing tape. This created an enclosed package that would further protect the object from fluctuations in the environment.

Applying sealing tape to top layers of sealed package

Wrapping and burnishing sealed package

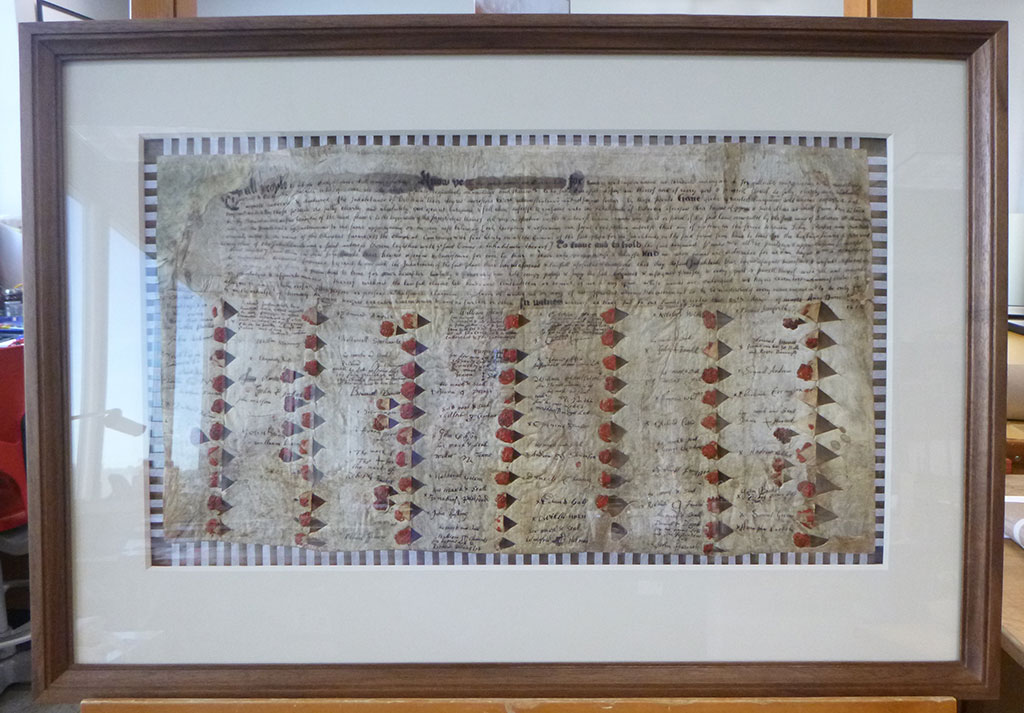

The sealed package was then placed in a wooden frame with a frame cap stained to match the main part of the frame. The whole package was sealed with wood glue and clamped shut until dry. As this piece would not be displayed vertically, there was no need to attach or make accommodations for hanging hardware.

Sealing of double-sided frame from the verso with adhesive, barrier board, and clamps

Sealing of double-sided frame from the verso with adhesive, barrier board, and clamps

The Great Deed after framing

Rehousing the Original

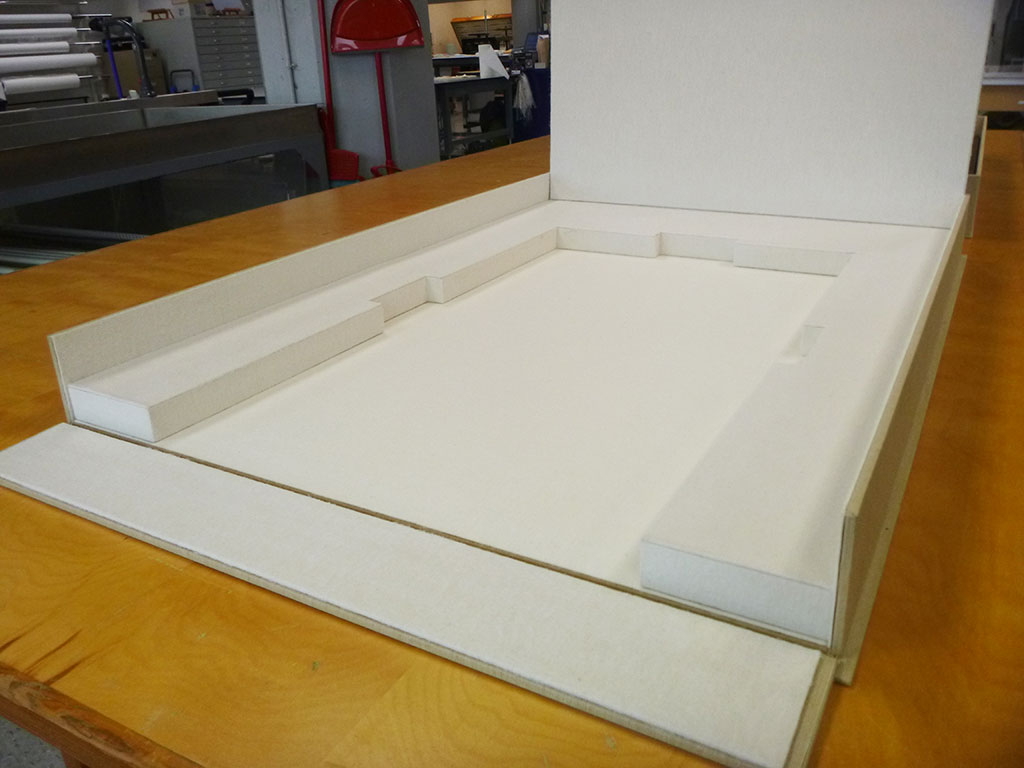

NEDCC commissioned PRAXIS Bindery to construct a custom two-piece cloth covered box with a leather label and interior furniture that would safely accommodate the framed deed and its original housing. PRAXIS lined the interior of the box with a soft archival felt and included a magnetic drop-down wall on one side for easy removal of the deed from the box. This format would allow for the original housing to remain with the newly framed deed in the town’s storage area.

Interior of box showing recess for original housing and lifting flap

The Great Deed and original housing in new two-piece cloth covered box

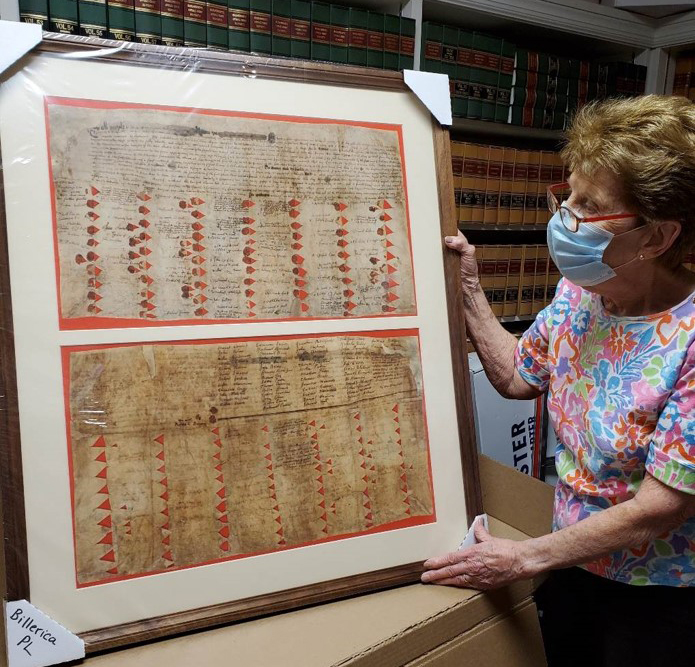

Returned and Accessible

With the custom housing completed, the Great Deed and framed facsimiles were couriered back to the Town of Billerica. The framed facsimiles are on permanent exhibit and can be seen at Billerica’s Town Hall and in the 1655 Room at Billerica Memorial High School while the original deed remains protected and securely stored in the town’s vault.

Town Clerk Shirley Schult unpacks the Great Deed in June 2020

Billerica Town Hall’s framed facsimile of the Great Deed during unpacking by Shirley Schult

THANKS

Many thanks to Kathy Meagher, Local History Librarian, and Shirley Schult, Town Clerk, for their help on the story and throughout the project. Additional thanks to the Community Preservation Committee and the citizens of Billerica for making this project possible. Thanks to Leftfield Project Management for funding the second facsimile print.

LEARN MORE

Want to start a Community Preservation Committee in your town? Find more details on the Community Preservation Coalition’s website, along with Technical Assistance and CPA Adoption in your community. While you’re there, check out Historic Preservation CPA Success Stories on historic preservation of all types.

Billerica Town History

Visit the Town Clerk’s Office on the Town of Billerica’s website, on Facebook @BillericaTownHall, or Twitter @TownofBillerica for Town updates and records.

Visit the local history page on the Billerica Public Library’s website, or follow the library on Facebook @BillericaLibrary or Twitter @Billerica_Lib for interesting stories and local history resources.

Story Notes

The treating conservator on this project was Katie Boodle. Digitization of the Great Deed and creation of facsimile prints was performed by Tim Gurczak. Specialized housings were created by Annajean Hamel and PRAXIS Bindery. Collections Photographers David Joyall and Nora Pfund assisted with the photographic documentation that was used throughout this article.

Story by Katie Boodle, Associate Paper Conservator, 2020